Travelling to Teach

19 Feb 2016

Mr A.N. Balagopal, who was one of the first teachers dispatched to Christmas Island in the ’50s, has vivid memories of both the hardships he endured and the joy he took in life on this remote outpost.

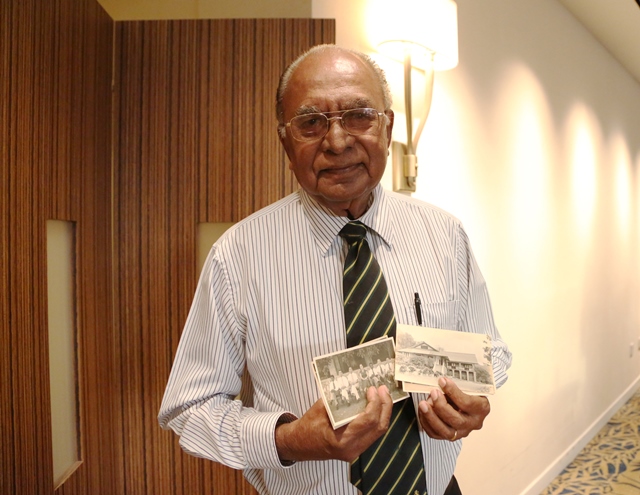

The first thing retired teacher Mr A.N. Balagopal excitedly displays during an interview to discuss his teaching experiences on Christmas Island is an old, black-and-white photo showing three men standing on a wooden pallet as it dangles from ropes high in the air. If any of the men – shown in the image encircled by luggage and even furniture – had lost his footing, nothing would’ve stopped him from plunging into the sea far below.

“There was no harbour on Christmas Island so you had to be lifted up to the jetty by crane!” he says, his memories from 1953 crystal clear despite his 85 years.

At the time, Christmas Island, a quarter the size of Singapore and 1,330km to the south, was administered and governed as part of the Singapore colony. The British held sway over Singapore and dispatched a group of about 30 Singaporeans to live on Christmas Island, where they worked as policemen, postmasters, administrators and teachers.

Mr Balagopal vividly recalls the perilous journey to the island from Singapore: a four-day odyssey on a smallish, 2,000-ton ship – about the size of a modern-day survey ship – which was equipped with first- and second- class cabins. “Europeans took the first-class single rooms, while teachers like me had to take the second-class cabins, which were shared among two to three people,” Mr Balagopal says.

The first three days of the voyage were pleasant, as the seas were calm. “You would come out of the cabin and look at the sea,” he recalls. “It was very nice, smooth sailing.”

But as the vessel emerged into the open Indian Ocean on the fourth day, the waves got bigger and the ship started rolling. “That ship had no stabilisers as it was a cargo-cum-passenger ship. I got seasick, throwing up and all,” Mr Balagopal says.

When the ship finally came within sight of its destination, Mr Balagopal had his first glimpse of the cliff – towering to a height of about 100 feet above sea level – that was the disembarkation point for the ship’s passengers. On why there wasn’t a safer means of getting ashore, he says, “Christmas Island is a very flat piece of land, which emerged from under the sea due to volcanic activity. Most of the shore is high above the sea and there are only a handful of small beaches around the island.”

Amid the spray of sometimes-towering waves as they crashed onto the structure where the jetty was anchored, the ship’s passengers gingerly made their way onto the wooden pallet. Secured by ropes to a crane on the jetty, the pallet with its cargo of uneasy island newcomers was winched to safety in a matter of minutes.

“Once we reached the jetty it was okay,” Mr Balagopal says with a laugh. “The jetty was like a warehouse and people were waiting for us outside.”

From India to Singapore

Christmas Island was the first permanent posting for Mr Balagopal, who had come to Singapore at age 23 in hopes of finding work as a teacher. He came armed with a degree in Physics and Maths from the University of Kerala and had been teaching in India when his brother, who had already spent nearly 15 years in Singapore, asked him to come over.

“The salary I was getting in India was about one-fifth what I’d get in Singapore,” Mr Balagopal remembers his brother telling him. “That’s why I wanted to come here!”

Not long after, he boarded a propeller plane with about 40 other passengers for the journey from Calcutta to Singapore’s old Kallang Airport.

Mr Balagopal had managed to arrange an interview with the then-Department of Education at Anson Road, where his interviewer was British.

“The interviewer said to me, ‘Would you like to go to Christmas Island?’ I said, ‘What? Where?’ Then he showed me on the map,” he recalls. “I think he asked me because nobody wanted to go! I said yes, mainly because I was a young man with no ties. Also, after a year on Christmas Island, we were to be granted leave to go on a holiday to Singapore or Australia and I wanted to go to Australia. So I accepted!”

The Christmas Island posting was unpopular because the two-year contract required the teacher to live and teach on an isolated outpost, cut off from their loved ones, with no entertainment and very little in the way of facilities or even communication apart from the occasional letter.

As Mr Balagopal had never taught at a Singapore school, he was first posted to Balestier Hill Primary for three months to work under some of its teachers.

The real adventure begins

Mr Balagopal soon joined five other teachers at the Christmas Island English School. In terms of the length of the school day, teaching methods and the curriculum, the school was much like a Singapore primary school of the ’50s. The school’s half-day sessions started at 7:30am and students took subjects like English and Maths.

That said, it was soon clear to Mr Balagopal that geographical distance wasn’t the only thing separating Singapore and Christmas Island. “Their standard of English was very low,” he says. “Many of them came into Primary 1 not speaking a word of English!” The school was the only one on the island for the children of its residents: roughly 1,500 Cantonese-speaking miners from Hong Kong and about 500 Malays whom the British had resettled there from Cocos Island.

“Fortunately, I was teaching Primary 4 or I would’ve had to use sign language. They mostly spoke Cantonese.” Mr Balagopal says. “I could speak Cantonese in those days, but now I’ve forgotten it.”

Teachers and students enjoyed a very close relationship as their living quarters were only about 100m apart in the island’s residential settlement, known as Flying Fish Cove. For two and a half years, Mr Balagopal stayed alone in one unit of a row of buildings.

“The children used to come to my house on weekends and mess everything up. I’d have to chase them away,” he says, laughing. “I would ask, ‘What are you doing?’ And they would say, ‘Just having a look, Sir.’ They had nowhere else to go!”

“Still, I thoroughly enjoyed the company of the kids. To them, I was not only a teacher but a guardian and a friend. During Chinese New Year, I had to visit all of them.”

Mr Balagopal would take his students hiking and camping in the jungle for three to four days at a stretch, searching for freshwater streams where they could catch fish. He also enjoyed conducting gardening classes with his young charges. “Because the land is so fertile, sometimes we’d have gardening classes and you could see something growing the next day!”

Island life’s ups and downs

Meals were relatively simple because, apart from the fish that could be caught in the waters around Christmas Island, everything else had to be shipped in on the boats from Singapore or Australia, which came once a month. “We had meat rations and we got frozen food from a Chinese stall. And because there was no restaurant, we all took turns cooking,” Mr Balagopal says. “So among the four bachelor teachers, if I had made breakfast one week, I wouldn’t have to do so for the next three weeks.”

A noteworthy perk of their posting was that all goods, like the beer that the teachers occasionally enjoyed during their off-hours, was duty-free. “There was no customs to collect duties so everything was much cheaper than in Singapore.”

The main drawback to working on Christmas Island was that there wasn’t much to do. Despite being a young man in his prime, Mr Balagopal had very little in the way of a typical social life. “When I was admitted to hospital for a sprained ankle, the nurses were friendly and I used to invite them out. But other than that, there was no dating. There was nobody there. Life could be dull.”

He recalls playing games like badminton and billiards in his free time.

Beyond that, Mr Balagopal made a habit of cycling around the island, occasionally swimming in its streams with friends or relaxing on one of its small beaches. He also relished the island’s Sunday and Wednesday movie nights. A screen and benches were set up in the open air at Flying Fish Cove, to allow the island’s residents to watch black-and-white films under the stars. “On Wednesdays, it was Chinese or Indian movies while on Sundays it was an English film. But I watched them all. What else was there to do? If it rained, I’d just wear a raincoat and watch.”

Australian handover

Though Mr Balagopal has never returned to Christmas Island since leaving in 1956, he treasures the years he spent there and wishes its ties with Singapore hadn’t been cut. In 1957, Australia gained sovereignty over the island from the United Kingdom in return for a £2.9 million payment to the Singapore government. The island’s residents all became Australian citizens.

“I really cried,” he recalls. “It’s such a beautiful place.”

Mr Balagopal went on to teach at Bartley Secondary, Gan Eng Seng School and Victoria School before becoming principal of Commonwealth Secondary School, a position he held from 1975 to 1987.

Though Mr Balagopal studied Physics and has been a Science teacher for most of his life, he has maintained a lifelong interest in History. He remembers every detail of life on Christmas Island – don’t even try to stop him once he gets started – and is passionate about relating his experiences there. He laments that young people don’t seem to know that Christmas Island once belonged to Singapore.

“Children must know this and they must know their history in general,” says Mr Balagopal, who recalls that when he was principal of Commonwealth Secondary, his efforts to persuade the better students to squeeze in some History classes alongside their courses in Maths or Science were mostly unsuccessful. The belief among students is that it’s easier to score high marks in the latter subjects.

“I know it’s ironic. Here I am, a Physics teacher telling my students to learn History. But it’s important. If you don’t know your History, you’ll miss a lot of things in life.”