Commonwealth Secondary School student Dini Syazwan dreams of flying. He got to know fellow schoolmate Marshall Chong who shares his passion for planes and the duo decided to build a remote-controlled plane.

“We had no idea how to build one. We’ve never done anything similar before,” shared Dini, a Secondary 4 student.

They watched YouTube tutorials and learnt to reprogram a remote controller to handle an RC plane. They also experimented with different materials before finding one that was light, yet sturdy enough for the body of the aeroplane. It took them more than a year and three failed prototypes before their plane finally took off.

They had help along the way. Teachers gave them tips, and they used the school’s Design Space – a room filled with tools, 3D printers and craft supplies meant for students get creative. It was the school’s way of nurturing innovation among students, offering resources that will aid their great experiment – not for academic results but simply in pursuit of an idea.

“We want our students to develop a mindset that sees beyond the short-term results of grades, that embraces experimentation and is not afraid to try, fail, and try again,” said Mr Nah Hong Leong. The science teacher heads Commonwealth Secondary’s Research, Innovation and Design Department, which spearheads the school’s efforts to drive innovation and develop creativity.

The importance of innovation

In an interview in 2017, then-Education Minister Ng Chee Meng said students have to innovate and find breakthroughs to thrive in this new era of technological disruption, but what exactly is “innovation”?

According to the Oxford dictionary, to innovate is to make changes in something established, especially by introducing new methods, ideas, or products. And for practical purposes, this idea or invention must grow into goods or services for which customers will pay.

But innovative ideas do not happen in a vacuum. Often, they are a result of creativity, discipline and a huge dose of appetite for experimentation and taking risks.

The best innovations grow to have wide-reaching impact on people and the world. For instance, tech giant Facebook, one of the most innovative companies of this decade, has drastically transformed how people interact with each other.

It has forced news outlets and brands to rethink their marketing strategies. It has resulted in new jobs in the digital space, such as social-media strategists and content creators – positions unheard of a decade ago. And it started with a simple idea: an online “place” to chat and share.

In a recent podcast, its chief executive Mark Zuckerberg said innovation is more than just having new ideas. It is very much about taking risks and trying new things constantly.

Facebook strives to be a place that encourages such behaviours. Zuckerberg’s employees often get together to build things – not just for work but also for fun.

How to develop the dream

Similarly, when it comes to getting students to be innovative, schools that Contact spoke with create opportunities for their students to try new activities and through the process, learn grit, resilience, cooperation and collaboration.

To breed innovation in the classroom you need to build a drive or an intrinsic motivation to keep students focused on it. One way to do so is to encourage exploration and imagination.

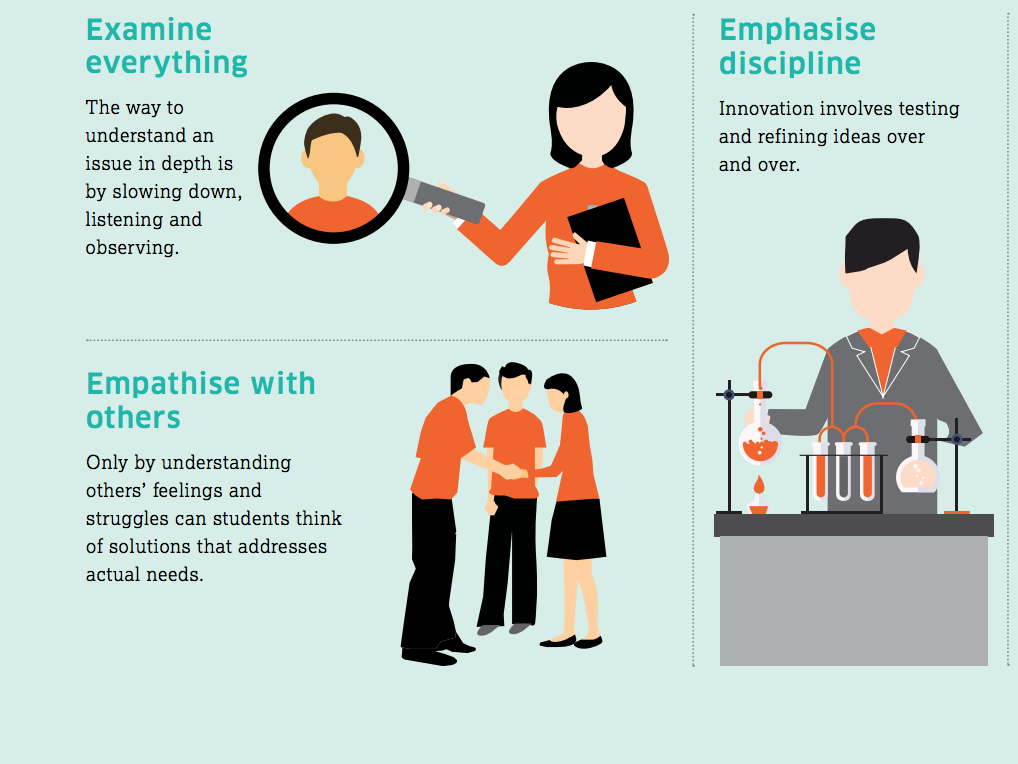

At Commonwealth Secondary, for instance, the school encourages innovation by exposing students to designthinking skills and mindsets from Secondary 1 by adopting the model developed by Stanford University’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, or “d.school”.

Students are introduced to the design-thinking methodology to get them comfortable with managing ambiguity and complex problems – a skill that will come in handy as they enter the working world in future, said then-Principal Aaron Loh.

They go through a five-step iterative process to figure out solutions to real-world problems: Empathise with users and their needs, define the problem, generate ideas, build a prototype, and test the model to obtain feedback. Activities are created to help students go through the process.

For example, to learn more about empathising with people, students are given a box filled with different everyday items that belong to their imaginary user. They have to look at the items – a coffee mug, a stress ball, photographs, for instance – and try to make connections and better understand the owner of the box.

When students are able to understand their users well, they can then begin to see how their solutions can bring value to others.

“Design thinking is focused on the experience and needs of the user, which makes the process very meaningful because through this deep understanding, you really want to make an impact on a person’s life,” said Mr Loh.

He shared how some students are working with disabled members of Friends of the Disabled Society, a non-profit voluntary welfare organisation.

They had been making simple handicrafts to sell, but sales have been poor. The students are now teaching them 3D printing and laser cutting to make their products more unique and sellable.

Creating the right environment

While the principles of innovation can be taught in bite-sized pieces, the spirit of innovation is also about getting students to make connections and find different approaches to the familiar.

At Haig Girls’ School, drama is used heavily in math lessons. Starting with a pilot programme in 2012, it was intended to enhance students’ knowledge of math concepts, but it also emphasises group work and encourages students to think of different ways to resolve issues – key traits that help foster innovation.

Ms Wong Yoke Lye, Assistant Year Head for Primary 5, who has been involved in the Teaching Through the Arts Programme from the start, said: “We noticed that our students struggle with math. They were easily discouraged and fearful of the subject. But they have a strong interest in aesthetics.”

Working with arts practitioners from the National Arts Council, Ms Wong and fellow maths teacher Ms Gina Cho developed ways that drama and dance can be used to understand concepts such as fractions, graphs, and money.

To learn about fractions, the students choreographed a dance where they assembled themselves in groups which then split up into smaller groups, to convey the idea of splitting up a whole.

To teach students about money, the teachers designed a carnival and got the girls to set up booths to sell things with “fake” money. “They learn about each other and tap on the strengths of their peers,” Ms Wong says.

“It’s inevitable that they get into conflicts with their classmates. But we have seen them resolving conflicts themselves and moving on to work towards a common goal.”

At Crest Secondary School, teachers found that students were not enjoying English lessons and were not motivated to do well.

Mrs Au-Leow Li Quin, who heads the English Language department, decided to get students to produce news videos as part of a News@Crest series.

“[English] lessons in class can be a little dry. The students don’t see the relevance, so we created this project where it’s more real,” said Mrs Au-Leow.

Students pick a topic they are interested to explore, act as broadcast journalists, and put together a news segment in the school’s media studio. One group produced a clip on the dishes sold in the school canteen, while another group featured the butterfly garden in the school.

The clips were then uploaded onto Facebook and YouTube for their schoolmates to view their work. The idea worked – students were excited with the project as it allowed them to be imaginative and experiment with something they had never done before. They also had to come up with content that their audience would want to watch.

Mrs Au-Leow added that the students had to take charge of the project from start to end, which gave them a sense of ownership and motivated them to work harder.

Judgement-free zones

Students need to be taught everything – including how to handle failure. The hardest way to teach it is to simply let them fail – something that goes against a teacher’s instinct to protect students. However, learning to overcome obstacles are crucial in the pursuit of innovation.

Ms Cai Xirui, who heads design thinking at Victoria Junior College (VJC), said: “There is the idea that you should fail earlier in order to succeed sooner. It’s a catchphrase that design thinkers use to remind themselves to not be afraid to try.”

During a study trip to San Francisco in the June holidays with her colleagues (see story “Walking the Talk”) to observe how schools there weave design thinking into the curriculum, she was struck by how the schools there believe strongly in the concept of a “judgement-free zone” – a safe environment that assures students that it is all right to fail.

A Santa Clara school teacher shared how she had once refrained from telling her students that their idea would not work, even though it was clear that the students were on a wrong path.

VJC Vice-Principal Gurusharan Singh, who also went on the trip, added: “[The teacher] knew that the students had come up with a wrong problem statement, but she withheld her judgement. She wanted them to find out on their own, and the students did eventually come to the same conclusion as the teacher.”

Teachers may feel compelled to help students avoid failure and get the right solution in the shortest time possible. “But it is important to let the students come to conclusions themselves, and decide for themselves what their next step should be,” he said.

This removes the stigma of failure and builds confidence in students who discover that they can do better. In a safe, judgement-free environment, students also learn to be open to ideas contributed by their peers.

How can teachers achieve this? “You can frame your feedback as questions, which invite students to think, instead of statements, which tell students that this is what they need to do,” said Ms Cai.

“To breed a culture of innovation, we have to leave things open-ended. This way, we encourage exploration,” Mr Gurusharan added.

Teachers experiment, too

Will all this lead to greater innovation? The results are not easily assessed and not visible in the short term. But at Commonwealth Secondary, the school has seen how its programmes can unlock the students’ passion to pursue and realise their ideas.

“We have seen students working on maker projects coming back on their own during the June holidays to ask that that the Design Space be opened up because they want to work on their projects,” said school principal Mr Loh.

Mr Eugene Lee, who is in Commonwealth Secondary’s Research, Innovation and Design Department, noted that teachers also have to be role models for students and learn to be comfortable with things they do not know.

“As a teacher, I often try to plan things and think them through until they are perfect in my head. But it doesn’t work out this way most of the time. The key is to learn to navigate ambiguity,” he stressed.

Said Mr Loh: “We know that more often than not, we won’t get it right the first time. But if we don’t do something, we’d never make a start. So, let’s just do it, and we will get better the next time and eventually, we will get it.”

Walking the Talk

For 10 days during the recent June holidays, a group of 11 teachers visited schools and companies in San Francisco to study social innovation and design thinking. Their key takeaway: Schools that want their students to be innovative must lead by example.

“If we want to be a school that talks about innovation and design thinking, there must be visibility in how innovation is practised,” explained Mr Gurusharan Singh, VicePrincipal of Victoria Junior College.

“It must be a culture within the school as well.”

On a visit to design and consulting firm IDEO, the group of teachers from VJC, Victoria School and Cedar Girls’ Secondary School, found that the company adopts innovative solutions to solve workplace problems as well.

For example, the firm noticed their staff were cycling to work and parking their bicycles outside the office compound. It was not ideal as the bicycles were exposed to rain and also at risk of being stolen.

IDEO solved this problem by designing bicycle parking lots using a pulley system to hang the bicycles from the ceiling. But this quickly gave rise to another problem – people started using the lots as storage space. They left their bikes in the office for days, inconveniencing other cyclists.

The company then came up with a simple process to identify errant users. All the bikes would be pulled down at the end of the week. IDEO would then inform owners who had not collected their bikes to do so.

Ms Cai Xirui, who heads Project Work at VJC, said the college has also being practising some of the principles of innovation.

For instance, the school’s operations manager would receive multiple calls to repair the same faults around the college. Or worse, some faults were not reported as teachers assumed that the operations manager had been informed by someone else.

“A committee of teachers tested a few ideas to make the reporting of faults a more transparent process,” said Ms Cai.

In one of the first few prototypes they came up with, the teachers created a notice board where people could write down the faults they had noticed. Everyone could refer to the board for updates. The simple method worked.

Now, as with everything else, the notice board has been upgraded to a Google spreadsheet that is shared among the staff. Ms Cai added: “I guess this is a small glimpse of IDEO in VJC.”

.jpg)

.jpg)