“Level up! Level up!”

Walk past classrooms in full action today and you may also hear sounds of students cheering like they were watching their friends on an online game.

Schools are steadily embracing educational games and gamification tools, where teachers may create custom quizzes or repurpose pre-made games to inject fun into their students’ learning.

Naval Base Primary School takes things one step further. As part of the school’s Applied Learning Programme (ALP) in Constructionist Game Design, which all students take part in from Primary 3 to 6, students get the opportunity to create their own digital educational games. Constructionism is a learning theory that anchors the programme, where students actively participate in creating a tangible product that is shareable with others.

As its name suggests, the ALP is centred on designing physical and digital games.

The school hopes that the programme will tap on students’ innate interest in games to encourage creativity, design thinking, multi-disciplinary learning, and development of increasingly essential skills like coding. It builds confidence too, as they will no longer be passive consumers but producers of games they can call their own.

“We hope students can make connections between different ideas and areas of knowledge,” shares Ms Malisa Bay, who is the school’s Head of Department of Aesthetics. “Learning can be further deepened when the product is something personally meaningful.”

Constructing purposeful products

While the mention of transforming primary school students into creative game producers may sound daunting at first, the students’ technical knowledge and capabilities are built progressively through their primary school journey, much akin to completing stages in games and levelling-up. In all, they learn what makes a good story, character design, visual styles, music, gameplay, and challenges and rewards.

It all starts at Primary 3, where one of the ALP’s interdisciplinary projects include students working in groups over a term of Art, English, Science classes and even Form Teacher Guidance Periods (FTGP), to brainstorm and create imaginary animals and their habitats. To get their creative juices flowing, students mould clay models of these animals, or even draw mood boards and illustrated posters as a form of world-building. Just like a game’s tutorial, or warm-up round, the students are made aware of the possibilities out there, and the only limit is their imagination.

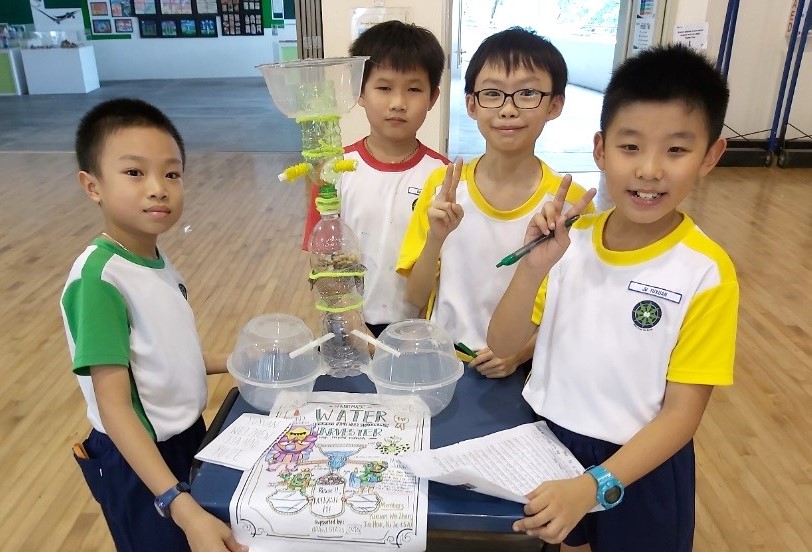

Students get their first taste of designing games for an actual audience in Primary 4, when they are challenged to design simple hands-on games and activities for their kindergarten counterparts at the school’s in-house MOE Kindergarten. From matching alphabets to forming words, to simple number-based games set in the solar system, they are posed with a challenge – to keep their game ideas easy to understand, yet attractive enough for the kindergarteners.

.jpg) Parents and MOE Kindergarten students visit booths set up by the Primary 3 and 4 students who exhibit and share their creations and games.

Parents and MOE Kindergarten students visit booths set up by the Primary 3 and 4 students who exhibit and share their creations and games.

What makes a good game?

When the students get to Primary 5, things start to get digital.

At Mathematics and Science lessons, for example, they learn some concepts through gamified processes and some gameplay. Along the way, they would be picking up storytelling skills through their language lessons, which are useful for developing game characters and story lines.

In Primary 6, all the learning culminates in group projects, where students must create an educational digital game suitable for their Lower Primary peers from scratch — from planning the storyboard, designing the in-game characters, composing appropriate music tracks and finally, programming their game to fruition.

Design thinking features heavily here: To better understand their game “users”, who are in Primary 1 and 2 , the Primary 6 students will revisit their Lower Primary days, going through Math and English worksheet samples for ideas and researching the digital educational games that their users are currently playing. Their takeaways and observations are helpful in their brainstorming, from understanding the need for larger font sizes of text, keeping the questions short and concise, to even minor details on when to share instructions. Various groups will then come up with eight to ten English or Math questions which their game will be based on.

While the plots and twists are being planned, the students also need to think of the graphics and music. Their Art and Music classes come in handy here, and students find themselves applying their knowledge about various art and illustration styles and consider adopting them for use in their games.

Their art teachers, for example, would introduce well-known paintings such as Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1889) and Lim Cheng Hoe’s Singapore River (1970), and students are challenged to incorporate and adapt modern game features such as buttons and progress bars to fit the classic art styles. Students are also introduced to characters from popular game franchises to explore various player archetypes, like warriors or cartoon characters.

When it comes to music, the students use GarageBand, a digital audio creation studio, to compose music tracks specific to their game. It goes beyond just composing a melodious tune; students decide on the mood of the music, be it grand, mysterious, or even dreamy. Other decisions to be made include the musical instrument which the track will be based on, and the various points of the game where the music changes according to the story, from the “conflict” to the “climax” and eventual “resolution”.

Meanwhile, they also pick up coding skills from trainers engaged by the school.

At every stage, their teachers pose user-centric questions to influence their decisions and vet their games’ relevance to their users. What are the characteristics of our younger peers? How can our game help improve and get students excited about English and Math? These decisions are made as a group, in the spirit of teamwork and collaboration.

Finally, months of hard work later, the students get to code and programme their envisioned game, on a free-to-use online programming tool called Scratch. The various pieces of the puzzle are fitted together, as the visuals, text and audio tracks are assembled based on the storyboard created. After testing to ensure that the games function well, teachers will upload the games as templates onto the school’s Student Learning Space platforms for the Lower Primary students to play.

The students are encouraged to model positivity by working in a sense of accomplishment at various stages to motivate the player.

The students are encouraged to model positivity by working in a sense of accomplishment at various stages to motivate the player.

Fun, fulfilment and maybe even career dreams

Dhiman’s group adapted Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night, adding their own unique touches to jazz it up.

Dhiman’s group adapted Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night, adding their own unique touches to jazz it up.

Students are required to journal about what they enjoyed about the project or felt they could have done better. One recurring theme in their journals is that of excitement, satisfaction, accomplishment, involvement, appreciation even – that their new-found knowledge and insights that has led to the creation of something close to their hearts and of use to their juniors.

Primary 6 students Dhiman Samarjit, Jayden Lo and Nydus Lin have been working together over the year on their game. Dhiman, who drew the game characters, remarks, “I have experienced coding games but this was my first time working with others. We had to learn to harness each other’s strengths and that made the experience meaningful.”

For Primary 6 student Chen Bao Bao, the ALP has influenced her aspirations. “I think the ALP lessons helped me understand how people who create games feel and how much effort they have to put in before their games are completed and ready to be played,” she says. “It is the first time in my life making a game. I hope in future, I can continue to create more games and to benefit others.”

.jpg)