If you ask students at Presbyterian High what they like most about their literature lessons, don’t be surprised if they say “hawker food” and “Singlish”.

They’re part of a growing number of students studying works by local authors and poets in English classes. They say that references to HDB life and school experiences make these stories relatable. This, to them, is a refreshing change from the Ancient Rome portrayed in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, and the American Deep South in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird—two iconic texts they’ve also studied.

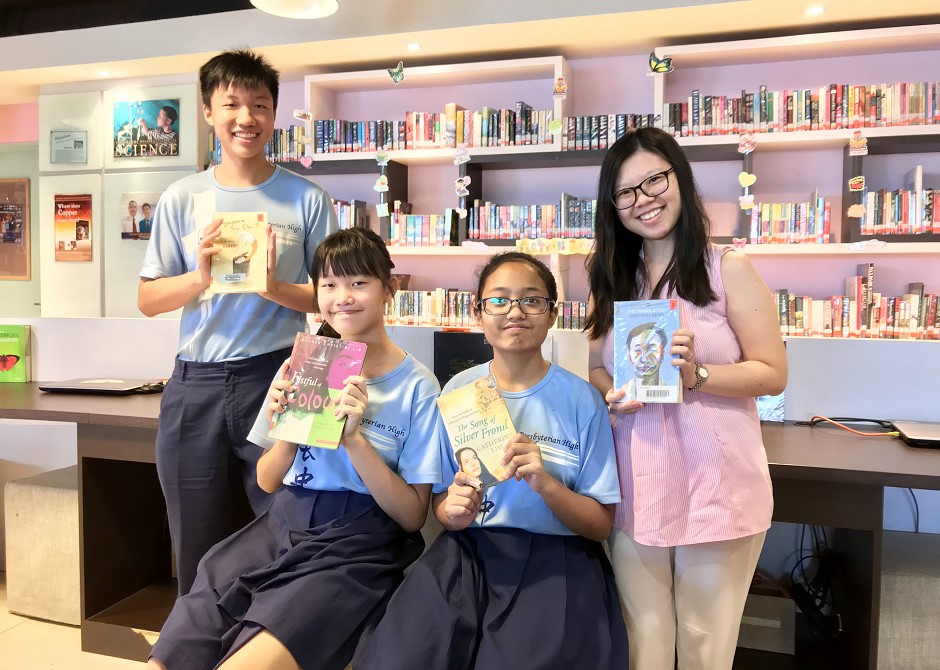

For many of them, school has also been their introduction to the growing field of Singapore Literature. Secondary 3 student Elyse Tan was surprised to learn that “the literature scene here is not as small as it seems”, and her senior Ethan Tan feels proud that that “even though we’re such a small country, we’re able to come up with such wonderful pieces.”

These “wonderful pieces” have consistently been included in MOE’s annual lists of English literature texts since 2007. Ms Meenakshi Palaniappan, Assistant Director overseeing the Literature curriculum explains that studying these texts “allows students to engage with national issues and perspectives, and expand their worldviews while developing personal notions of self, national and cultural identity.”

Window on Singapore society

True enough, in her four years at Jurong West Secondary School, Kelly Chew has delved into stories about the mentally ill in Singapore, the treatment of domestic workers, and even capital punishment. It’s a far cry from the 19th-Century Western classics she used to read as a child, such as Black Beauty, which she treated as a form of escapism.

She finds the local texts she’s studied to be “eye-openers”, because “while the language and setting are relatable, the stories show what it’s like to be in the shoes of someone living in the same country as you, but facing problems you have never experienced.”

Likewise, Elyse found that studying seminal play Emily of Emerald Hill, about an elderly Peranakan matriarch, made her realise that women here have a come a long way from when they were expected to stay at home, do chores and take care of the family. It made her more appreciative of cultural heritage, which “makes us who we are today.”

Connecting literature to life

Teachers welcome the move to introduce more local works in the classroom. Kelly’s teacher, Ms Orry Zhang, sees it as an opportunity to help her students “establish their sense of identity” by studying “universal themes with a local context”. As the head of her school’s English Literature team, she makes sure that every cohort in her school gets to study some Singapore works.

For Ethan’s teacher, Mrs Audrey Fernandez, teaching Singapore Literature means she can easily draw connections with things students are familiar with. When discussing Terence Heng’s poem “Postcards from Chinatown” on the commodification of Chinatown, she collected tourist advertisements of the district, and compared them to archival photos taken in the 1960s and 1970s.

When discussing Stephanie Ye’s “City in C Minor”, a short story about someone who put aside her dream of being a musician in Singapore to take up a scholarship to study economics, Mrs Fernandez took the opportunity to sit down with her students and ask them about their own dreams.

For some students, the dream is literature itself. Inspired by the authors she’s studied, Presbyterian High’s Haney Ashera Taib wrote a 102-word flash fiction about a mannequin’s feelings as it silently observes customers in a store. It won a prize at last year’s National Schools Literature Festival.

Her schoolmate, Elyse, hopes to publish a book of her poetry and prose, and is working on a manuscript. She’s been sharing her work with her teachers to get their feedback, and even has her sights set on a particular publishing house. Knowing that there is so much opportunity in Singapore Literature, she says “I feel like I’m not alone. I feel empowered, and knowing that we can do great things.”