Imagine being at a murder scene. You move around to find traces of the malignant act. The clock is ticking, and you need to act fast to solve the mystery.

There is only one peculiarity about this ghastly scene: everything is taking place in virtual reality (VR) within a computer lab.

That’s the experience of students taking the Forensic Toxicology and Poisons elective at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

They don a VR headset to be transported into a virtual crime scene – for instance, a bedroom. Once inside the ‘room’, students use wireless controllers to navigate their way, picking out signs of foul play, such as bloodstains on a bedsheet or mysterious substances inside knocked-over bottles, for example.

This programme’s concept was developed by Associate Professor Stella Tan Wei Ling and the NUS Forensic Science team. They worked with the Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) Imaginarium team at the NUS Libraries to roll out the programme. The TEL Imaginarium works with NUS staff and students to implement immersive tech tools like VR into their research projects.

As the Academic Director of NUS’s Forensic Science programmes, Prof Tan says that she is always on the look out to make the modules more engaging and relevant to her students.

“In this module, our students learn to investigate medical causes of death or substance-induced poisoning, then build their case and present their hypotheses. I wanted to use VR to make learning more fun and immersive so they can better appreciate these forensic techniques,” says Prof Tan.

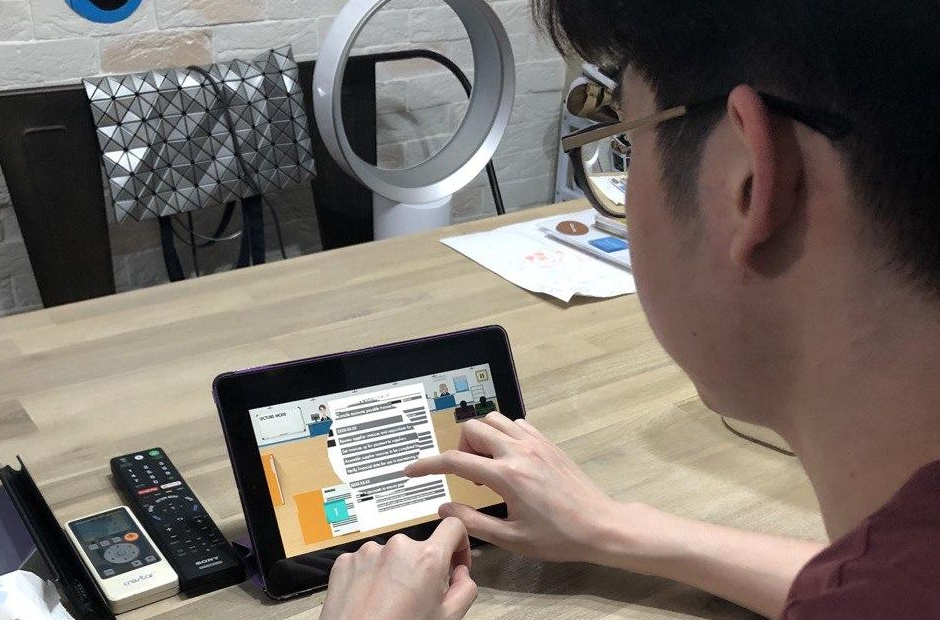

A mocked-up crime scene created in VR

The module runs for 10 days and has attracted NUS students from various disciplines. Prof Tan says that law students take it to appreciate the value of evidence, while nursing students learn about the effects of different poisons.

Sleuths-in-training

The VR lessons are conducted inside TEL’s Green Room, which houses the technical apparatuses. The students work in teams. One student wears the headset and navigates through the simulated environment while the others track the progress via a monitor screen.

“VR has made learning more hands-on and intuitive,” says Shaphyna Nacqiar Kader, a final year Bachelor of Science in Chemistry student. “When I wear the headset, I am fully immersed in the virtual environment. I also get a fuller picture of the crime scene, and I am able to spot subtle clues more clearly, such as handprints, for example.”

Apart from the immersive aspect of these lessons, VR has brought other benefits. For instance, Ms Tan mentions that the use of VR has encouraged students to develop their teamwork skills. “Because this VR system allows fellow students to see the headset wearer’s field of vision, teammates can direct the headset wearer to pick out details or clues he or she may have missed,” says Ms Tan.

It also provides an opportunity for instructors to get deeper insights into the students’ thought processes. “When the students are describing what they see through the headset, we can better assess how they approach the scenario,” says Prof Tan.

She adds that when the students are interacting with each other, they can sharpen their analytical skills and correct each other’s methods on the spot.

These exercises play an important role in preparing students for the real world, says Prof Tan, as crime scenes are often time-critical situations. “Hence, instead of just reading about treatment methods, experiential learning trains students to think and act on the spot.”

Simplifying the process

Before VR entered the picture, setting up a mock crime scene was a laborious process, says Prof Tan. The students and professors would put together a physical set and furnish it with props such as tables, chairs and beds. Then, they would have to plant the clues. Once the students finish their investigation, the scene would have to be reset to its original configuration.

Now, with VR, this “can be done within a matter of seconds, through a few clicks of the mouse”, says Prof Tan. The programme also allows students to check if they have chosen the right answers and gives them a score, so they understand where they may have erred.

Bringing it back home

VR lessons work for Home-Based Learning (HBL) too. Prof Tan says, “With VR, students can loan the headset during HBL, complete the experiment in their home and post their results online. After that, you clean the headset and mail it back to the school.”

Shaphyna says that she has already conducted a VR-based experiment at home, albeit a more rudimentary version. She recreated a crime scene by planting clues in her bedroom. Then, she took a few 360-degree images of the room from different angles and, using a software, put them into VR and tagged the clues.. Then, she attached a pair of cheap VR glasses to the screen of her phone so she could view the image in 3D.

Shaphyna Nacqiar Kader’s homemade VR experiment. The top images show a 360-degree view of her room (left) and her room as seen in VR (right). The bottom images show her VR googles attached to her phone (left) and a screenshot from her VR experiment (right).

“This allowed me to turn my bedroom into a 3D ‘crime scene. I then sent out the project to my fellow course mates to work on. The goal was to find the criminal evidence within two minutes,” says Shaphyna.

“My VR experiment had limits — objects within the crime scene couldn’t be picked up. But the 3D image helps students examine the crime scene in greater detail. For example, students can better analyse how each piece of evidence relates to the other by assessing their positions in three-dimensional space,” she says.

Work-in-progress

VR-based lessons are still work-in-progress and there are things it cannot simulate yet, says Prof Tan.

She says that there are aspects of navigating a crime scene that require finesse.

“For instance, you need proper techniques to handle the evidence or else you risk damaging them. Right now, we are using controllers, which are essentially just joysticks and can’t fully simulate the flexibilities of a human hand,” says Prof Tan.

“These restrictions notwithstanding, I think VR plays an important role in how we teach forensic sciences now. Using VR, we will be able to finetune how we test students when they operate in this framework, so that we can assess their aptitude,” she says.

“This also allows students to have more fun while they are learning. And when they are more engaged, I think they will be able to appreciate the relevance of their subject better,” says Prof Tan.

7e3680a7a8a66eb2afccc900c73e6f2e.jpg)