I remember the day I came home heavy-hearted after my Secondary 2 Mathematics mid-year examinations. One of the many subjects that I was sure to excel in would now be a major let-down – in my haste and smugness, I had missed a whole page of questions in the exam paper!

My poor mother bore the brunt of my carelessness, as I wailed and ranted to her for the rest of that day. All because I would no longer get that A1 I so wanted. On another occasion, I remember the voice of my History teacher booming at me to stop writing, as I tried desperately to squeeze just a few more words into that class test as if my life depended on it (no it didn’t help my score and I wailed some more).

Further back in primary school, I used to revel in my teacher’s praise for scoring full marks at my Chinese tests. Since I’d always been reserved by nature, I saw how grades was a way to be “noticed” , and wound up pegging my esteem entirely on maintaining that gold standard.

In the end, school life for me was a self-imposed pressure cooker. My parents were innocent – they merely affirmed my efforts and conveyed my teachers’ congratulations for my squeaky-clean record. It was I who drove myself hard, striving to clinch every possible victory. All for the sake of securing good grades, thinking that that was the sole purpose of schooling. Little did I know how much I was missing.

I wouldn’t learn beyond what would be tested

My obsession with scoring well led me to ‘study smart’ and cling on to sure-win strategies. I would memorise Chinese idioms – up to 150 of them prescribed in the curriculum – and made sure I used as many of them as I could in the essays I wrote. I would even pick topics that allowed me to maximise my idiom count (I know this sounds insane!)

My penchant to perform constrained my thirst for knowledge and writing abilities. Gradually, I would ‘spot’ questions and only studied topics that I was sure would be tested. For one of my Geography Elective tests, I only studied the topics of Agriculture and Tourism, as I could simply choose these two topics in the O-Level exam.

As for Additional Mathematics, it became a routine of attempting the same type of questions over and over again. I enjoyed ‘solving’ these problem sums, but not new and unfamiliar ones that I had to crack my head over. Perhaps it was just the thrill of being right and a full score – as long as I could fall back on tried-and-tested ways of studying that were familiar and predictable, I didn’t care for the rigours of the problem-solving process per se.

My desire to perform stemmed my curiosity for things that stirred my interest but weren’t going to be tested – I found hydroponics as a way to grow vegetables fascinating, but wouldn’t try it out for fun and experimentation at home because there was no direct pay-off for my scores.

Looking back, I could have grown in agility as a learner and a more creative problem-solver but no, I was after an exam mark at the expense of expanding my horizons.

Running the rat race, all by myself

My quest for success in school also made me see others as competitors. I would try to outdo my classmates in tests and exams, comparing our scores and pitting our wits – from maths solutions to Literature analyses, and even teachers’ remarks on our daily work.

Learning, for me, was a race to run, a competition to win. As a result, I shunned study groups and eschewed group work, seeing them as an unproductive use of time. I preferred to study on my own and have more time to make my own notes. Besides, working and studying with others seemed intimidating for an introvert like me. All this led me to choose a junior college not for its school culture or activities or even the healthy competition, but where there were rivals I could trump.

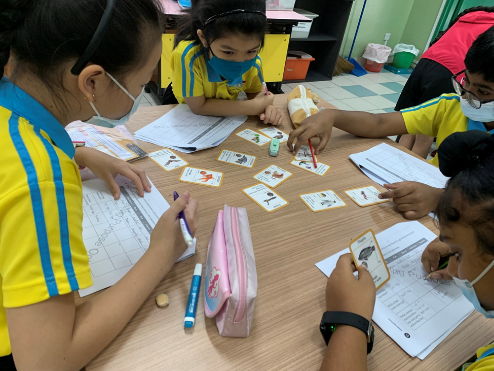

I could not see the value of interacting with my classmates, hearing their views and having my assumptions challenged. Only later, in my 20s and wiser, did I realise that I missed out on some of the best parts of schooling – finding support in one another through our struggles, sharpening each other’s understanding of concepts, and honing confidence and resilience through challenging assumptions and making mistakes.

Education is not meant to be a self-centred, solo endeavour. Who knows what I could’ve gained from a few (friendly) debates with my classmates, which might have drawn me out of my shell? Or what a few stories exchanged during our study groups could have done to help us understand a literature concept better?

If I could turn back time

My schooling journey might have given me academic success and set me on paths to reputable institutions, but with the attitude I carried, I was none the wiser when it came to the basics like taking risks, public speaking and thinking out of the box.

If I could reset my education journey and go back 20 years, what would I have done differently? How would I encourage my future children to learn?

1. Embrace learning as a communal activity

Collaborating with others and negotiating differing views can be a good exercise in empathy and perspective-taking. Pitching ideas to group mates can train up courage and persuasive skills. Enjoying a game or sport together can bring out the team player in us. With these attributes, I’m sure I’d be more comfortable today at meetings and in workplaces, where soft skills sometimes count for more than technical competencies.

2. Go beyond the textbook

Lectures and textbooks should be regarded as a starting point that sparks discovery of the world beyond. Instead, I made them my world. Since the application of knowledge is more valuable than knowledge itself, when I learn about compound interest in Mathematics, I could find out what it means for the money sitting in my bank account. When I learn about food composting in my Science lessons, I could venture further to watch my school canteen vendors in action. In this world of complexity and uncertainty, answers are rarely readymade and spelled out neatly; they are better found through an insatiable quest for knowledge.

3. Be willing to fail, and try again

I grew up hearing this advice to “pick myself up when I fall”, but truth be told, I don’t take chances and have never allowed myself to fall, or fail. By denying myself that experience, I set unrealistic expectations.

I expect a rulebook for every adulting situation and where there is none, I don’t quite know how to proceed and am not as quick on the uptake as my peers. And in my work as a writer, which requires me to pursue story leads, interview people and make tough calls on my own, so much is new for me and the uncertainty makes me flinch, to be honest.

Am I doomed to failure? It would be an opportunity to grow! Since I know I can’t dodge failure forever, I have decided I would be better off learning – finally – to take it by the horns.