Do you think mental health is an increasing concern among youths?

Wei Hong: I think youths are more aware of mental health issues like depression and anxiety. Some of my peers have these conditions. Many of us are staying at home a lot more because of COVID-19. With activities going online and safe distancing measures in place, it’s harder for youths to keep up social interactions with their friends. This means there are fewer avenues for us to share our stressors and worries with people we typically reach out to.

Mdm Soh: Yes, for sure. Other than what Wei Hong shares with me, I have also observed that youths seek help more readily. I have worked with patients in various clinics over the past 20 years, and in recent years, especially with COVID-19, the number of people coming forward seems to have increased.

What do you think youths these days are stressed about?

Mdm Soh: Their future – jobs, studies. From a young age, parents send their children for tuition and enrichment classes so that their children can be ahead. This pressure to do well may become ingrained in their children, who grow up worrying about doing well in school, scoring well in exams, getting into ‘good’ schools, and eventually finding ‘good’ jobs in ‘good’ companies.

Wei Hong: I definitely agree that academic stress is one source of stress for us. I also think that the need to conform to parents’ desires is also stress-inducing. For example, as youths, we may want to pursue an interest or passion, but our parents want us to do something else. If we choose to go our own way, we could face pressure from our parents, or heap extra pressure on ourselves to not fail. If we choose to conform to our parents’ wishes, it may be an unwilling compromise. Either way, it can be stressful not just for the child but also for the relationship.

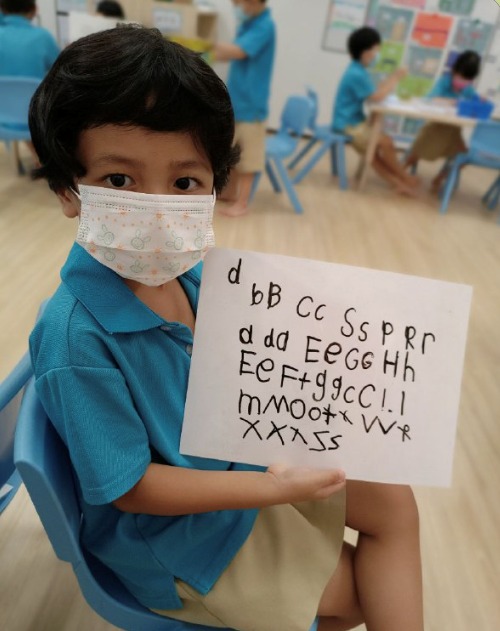

Mdm Soh and Wei Hong, when he was 9 years old. Mdm Soh believes that regular conversations and good communication between them from an early age built a strong relationship that enabled her to help her son deal with issues he faced later in life.

Has Wei Hong told you about any issues he faced with his mental well-being before?

Mdm Soh: My husband and I believe in good communication and we started having conversations with Wei Hong since he was young. We’re always asking ‘How are you? How was your day? What did you do with your friends?’, and we always make time to listen. Recently, he told us about some issues he was facing, which he didn’t know how to solve. We tried to solve the problem together, but it didn’t work out. So, I told him, ‘Why not talk to someone else who can help?’ and I helped him to find someone else to talk to.

Wei Hong: When I feel sad or overwhelmed, I usually try to deal with it on my own first. I like going for a run – it gives me an endorphin high. I feel more energised, and my thoughts are clearer afterwards. It’s a good coping mechanism. But running won’t solve all problems, of course. I also look to my mum, my family, and friends.

What are your thoughts on seeking professional help?

Wei Hong: My mum encouraged me to see a professional when we both felt that I would benefit from it. Singapore is now much more progressive in terms of being more open to mental health issues. I don’t feel like I need to hide the fact that I seek professional help. In fact, it feels good to see a professional. Having another listening ear is a great option and they are excellent listeners!

Mdm Soh: Yes, I encouraged him to do so. It’s not only for young people, too. I have a friend who is almost 70, and she asked me for recommendations as she wanted to see a professional therapist. She said that after her sessions, she had a better mindset and clarity of thought. She was able to deal with her problems and find solutions. If a 70-year-old aunty isn’t shy about seeking help, I think young people shouldn’t be too.

What do you think parents should be more aware of when it comes to youth mental health?

Mdm Soh: It starts with spending enough quality time together. Knowing little things about our children is important. I like to say that if I don’t even know which drink Wei Hong likes, how would I know what are the problems he’s facing? We all know that there are only 24 hours in a day, and with work and school, there isn’t much time to spend together. For the time we have with our children, we should try to converse more, learn to understand each other better, and it’ll form the foundation of good communication. Eventually, as our children grow older and face more complex problems, that communication channel remains open for them. Mental health problems are not always plainly visible. Oftentimes, we can only offer help if we know our children well enough to spot irregularities in their behaviour, or if they allow us to know about their issues.

Wei Hong: I’ll share the sentiment I gather from my peers. It’s mainly about stigmatisation. In my parents’ generation, mental health is not a common topic. They may say that stress is part and parcel of life, and impose this mindset on youths. Youths may think, ‘What’s the point of talking to my parents?’ Talking about our own mental health is not easy. It’s an emotional and sensitive topic, and it can feel intrusive. If parents treat mental health issues that we raise to them as part and parcel of life, and tell us ‘Don’t think so much. It will pass’, this response may cut off future communication on the topic. We feel that we’re baring our soul, but parents are just brushing us off. It may result in youths not seeking help, and the situation may escalate. On the flipside, parents may not want their children to be labelled as someone with mental health issues. No parent wants to see their children being stigmatised by society, so there’s some denial. It’s a fine balance and I think it’s important to listen and empathise.

For more information on students’ mental well-being, take a look at these resources.

.jpg)