The English teacher holds a stack of compositions written by her Primary 3 class. As she hands out the compositions to the students, they immediately check for their results.

But where are the marks? “Teacher, did you forget to give us our marks?” one child asks. No, she didn’t. In place of scores, she gave more detailed comments than they were used to, on how to improve their writing. She gives them time to look over the comments and tells them to approach her if they need clarification.

The students were expecting to take on a new topic for their next assignment, but to their surprise, they were asked to rework the compositions with the feedback in mind.

What’s the change? There is more time for these learning opportunities now, says Dr Karen Lam, the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) Master Specialist of Assessment Policy and Practice. By reducing the number of exams per school year, schools are spending less time preparing for school-wide exams, and are reporting an overall increase in opportunities for deeper learning and development in their students, she adds; this is what MOE was aiming for.

Learning beyond tests and grades

Since 2023, mid-year examinations have been removed for all primary and secondary school students. The same change kicked in for junior colleges this year. In addition, Primary 1 and 2 students do not sit for any exams and instead of grades, receive qualitative feedback on their progress from their teachers.

These changes are part of the Learn for Life movement to nurture our students to be confident and self-directed learners. The removal of mid-year examinations is another step away from an over-emphasis on academic results and towards prioritising school experiences that provide joy of learning for students.

As part of the shift, teachers have tweaked the way they assess students’ works, with more in-depth comments that encourage students to reflect and act on their learning process.

“Our focus is on teaching and learning, and helping students develop core competencies. We want to move away from teaching solely for the test,” shares Dr Lam, referring to the traditional habit of designing teaching around exam goals and calendars.

She cites the earlier example of how the teacher had more leeway to teach to the students’ needs. “By giving detailed and targeted feedback, we are encouraging students to think about their own thinking and learning, also known as metacognition. We don’t want them to look only at the marks they have received.”

‘More testing does not equate to more learning’

The move to reduce emphasis on exams has, however, prompted some parents to wonder if their children will be adequately prepared to sit for major exams such as the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE), N-Level and O-Level examinations.

Dr Lam offers another perspective on this: More testing does not equate to more learning.

Exams are unable to provide the holistic information on students to assess if they are effective learners or have the necessary future-ready skills, especially 21st Century Competencies like Adaptive and Inventive Thinking, she explains.

To get a more well-rounded view, captured across the school year and not just at two or three critical junctures, teachers have been using a range of assessment methods and tools such as quizzes, dialogue sessions, and ongoing assignments in class and via MOE’s online learning portal, the Singapore Student Learning Space (SLS).

Here’s how a teacher may deploy this:

- Pop quizzes to gauge readiness: To quickly gauge how well a class has understood a new chapter, the teacher designs a quiz with a handful of questions. Such pop quizzes offer instant data on the areas of clarity and doubt, and the readiness of the class to move on to the next topic.

- Group review or 1-to-1 coaching: If most of the students struggle with understanding a new concept, the teacher may get them to review their steps and identify the problematic areas. But if only a handful of students need help, the teacher may opt to work with them individually or in a small group while the rest of the class work on assigned tasks, or she could pair students up and get the stronger ones to coach the weaker ones.

These strategies build in opportunities for students to grow as independent learners.

Dr Lam notes, “Teachers use the information they have received through a range of sources from the different assessments to make decisions about how to plan their next lessons and to address learning needs.”

Removing mid-year exams also frees up more time and space for teaching and learning – the process of carrying out a school-wide exam for all subjects takes around three weeks, including the preparation and marking time.

“During the exam period, all teaching and learning would have to stand down,” she says. “But now, this time is not blocked up by the exams. Schools have the flexibility to be more creative with the scheduling of lessons or school-wide programmes, and students have more time to learn life skills and develop interests.” These efforts in turn lead to more engaged students who are ultimately better able to manage when the exams come around.

Exams still serve a purpose, hence the year-end exams remain compulsory for students in Primary 3 and above. “Exams tell students how they have consolidated their learning for the year,” adds Dr Lam. Exams have also evolved, moving away from assessing the recall of knowledge to test thinking skills instead.

Students should want to learn, not be pushed to learn

More important than aceing their tests, is the need for students to develop an intrinsic motivation towards learning. Over the years, MOE has sought to emphasise students’ holistic development, and the policy reforms bear that out.

Significant changes in the last 12 years include the abolishment of rankings for secondary schools and junior colleges, changes to the scoring system of the PSLE, and the implementation of subject-based banding to replace streaming for secondary school students.

As with the removal of mid-year exams, the message from MOE is clear: by scaling back the over-excessive focus on academic results, students are encouraged to view learning as a journey of growth and self-development, not a competition with others.

“We want to see them better themselves because they are pushing their ideas and their interests forward. This is the long-term perspective that will prepare them for life.”

Dr Lam, who has been working on assessment policy at the MOE for the past 10 years, and advocates for more opportunity for deep learning in schools

“Ultimately, students are in competition with themselves, and not others,” says Dr Lam. “We don’t want students to feel motivated to learn only because of the competition or because of the examination.”

“We want to see them better themselves because they are pushing their ideas and their interests forward. This is the long-term perspective that will prepare them for life.”

These policy shifts have sparked change in more ways than one.

At one primary school, its principal embraced the spirit of empowering students to take charge of their learning.

He flipped the format of the school’s twice-yearly parent-teacher meeting: Instead of teachers giving feedback to parents on the child’s performance for the term, the students were guided to lead the conversation, by sharing with parents and teachers their reflections and learning goals.

The students have been pulling this off with aplomb, to Dr Lam’s delight, and this practice has been common in many primary schools since the 2009 recommendations of the national Primary Education Review and Implementation committee to involve students more in the learning process.

“In this case, you have the children articulating their reflections and setting goals for themselves,” she says. For students to be self-aware and have agency over their own development and growth, is the kind of assessment practice she hopes to see in the years to come.

Q&A: How do I know my child is learning?

1. “In the past, the mid-year exams would provide me with a good gauge of how well my child has learnt. Without the exams, how can I know how my child is progressing?”

Suggestion: Parents could encourage their children to talk about their daily learning experiences, and discuss the feedback given by teachers in response to the daily work, weighted assessments and other tasks, says Dr Lam. Parents could also work with teachers where further support is needed. They can encourage children to identify their strengths and areas to work on, as well as affirm their efforts.

2. “I used to rely on the mid-year exams to help my child plan and review his work. Now, it’s a lot to consolidate at the end of the year. How can I better support my child?”

Suggestion: There is no need to load children with excessive additional work. What is more useful is to guide the child to regularly review the feedback given by teachers, says Dr Lam. Parents can guide their children in planning the schedule to revise their learning in the lead up to the exams, and help children to concentrate and be focused during revision as they work on revision tasks and questions, while providing emotional support and assurance.

3. “I used my child’s exam grades to motivate him. Is there a better way?”

Suggestion: Every child is unique and has particular strengths and areas for growth. Children can be motivated when encouraged to develop in their strengths and abilities, while being supported to identify the steps they can take to progress in their areas for growth, says Dr Lam. Parents can appreciate their efforts, and celebrate their progress and successes, whether big or small.

Case study: At Oasis Primary, they learn geometry from a different angle

Photo taken when Covid-19 pandemic safety measures were in place.

At Oasis Primary School, time and space from the removal of mid-year exams has inspired more creative and effective lessons from its teachers.

Maths teachers have used the freed-up time to deploy what is known as the “flipped classroom” concept for their Primary 6 classes.

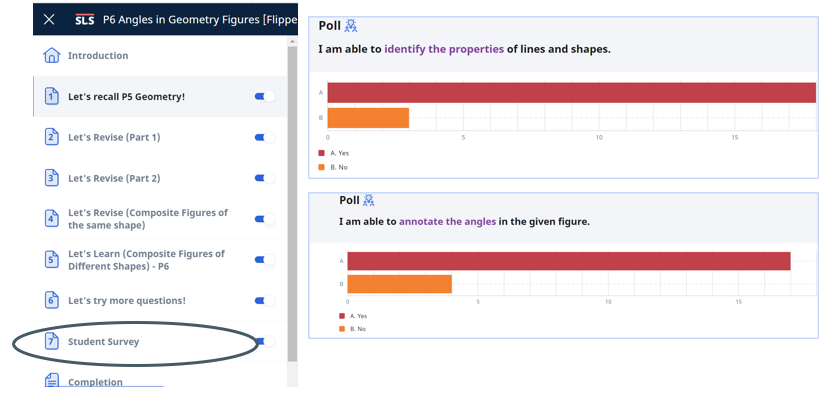

To teach geometry, for example, they first gauged how much students retained of their Primary 5 geometry knowledge, and designed an assignment on the Singapore Student Learning Space (SLS) for students to pre-read and watch. Their answers, obtained through polls or marked by the portal, provided crucial information about each student’s learning gaps.

By the time they step into their classroom, the teachers would have already prepared materials and activities that are more tailored to the students’ needs.

In short, teachers are designing lessons that assess and respond to their students’ learning.

In turn, these experiences are encouraging students to take charge of their own learning, notes Mrs Melissa Wee, Head of Department for Mathematics at the school. Lessons can also be enhanced with feedback tools and videos to “offer chances for students to engage in reflection and self-assessment”, she adds.

By harnessing technological tools like SLS, teachers are better able to monitor the students’ thinking process, which also becomes more visible to the learners themselves, explains Mr Pierre Fong, the school’s Head of Information and Communications Technology. Students can also assess one another online, he says, as providing feedback to their peers encourages students to think deeper about their solutions.